Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion

This is not a book about influence in the professional work. It is more about raise people’s awareness about the influence tactics people are exposed in their daily life, though these tactics can be used in the professional work.

This book described a number of psychological tricks that can influence or control people to take actions in the way we except. Although the books has 500+ pages, the core is around 50+ pages. The main idea of this book is to express that human being (or animals in general) has some “hard-coded” fixed-action patterns (described as “click, run” in this book).

These fixed-action patterns were developed during evolution to help the animals quickly and efficiently take reactions when facing some urgent situations. In natural and non-adversarial environment, those patterns are highly effective and with low false-positive rate. However, they can be and have already be leveraged in modern society due to their deficiency. These fixed-action patterns are categorized and each of them comes along with a large number of examples as evidences to demonstrate how they can be leveraged.

By reading the chapter titles alone, the readers should be able to know the tricks conveyed in this book by 30%. If read the first few pages per chapter and the descriptions of the variants of the tricks, 80% of the information can be absorbed. If further read 2-3 stories per trick, the readers should be able to know how to leverage those tricks. The ROI of reading all of the stories is low, at least for me. Another efficient way of reading this book is to first read the summary of each chapter. And then selectively read each chapter or part of a chapter in details if interested.

Notes

Chapter 2: Reciprocation: The old give and take

Rejection-then-retreat technique, although it is also known as the door-in-the-face technique. Suppose you want me to agree to a certain request. One way to increase the chances I will comply is first to make a larger request of me, one that I will most likely turn down. Then, after I have refused, you make the smaller request that you were really interested in all along.

If the first set of demands is so extreme as to be seen as unreasonable, the tactic backfires. The truly gifted negotiator, then, is one whose initial position is exaggerated just enough to allow for a series of small reciprocal concessions and counteroffers that will yield a desirable final offer from the opponent.

The rejection-then-retreat procedure won’t harm future negotiations.

Defense

- We can avoid a confrontation with the rule by refusing to allow a requester to commission its force against us in the first place.

- Perceive and define the action as a compliance device instead of a favor, the giver no longer has the reciprocation rule as an ally:

- Provide aid in return.

- Recognize the ingenuity of the favor and redefine it as a trick.

Chapter 3: Liking: The friendly thief

People prefer to say yes to individuals they like. The liking rule will take effect even when the social bond is not present at the moment.

Professionals seek to benefit from the rule even when already formed friendships are not present for them to employ. Under these circumstances, the professionals make use of the liking bond by employing a compliance strategy that is quite direct: they first get us to like them.

Make oneself to be liked

- Physical attractiveness.

- Similarity: physically similar, similar interests, similar behaviors.

- Use the language of the audience.

- Compliments: When people flatter or claim affinity for us, they may well want something. If so, they’ll likely get it. this tendency held true even when the men fully realized that the flatterer stood to gain from their liking of him. Unlike the other types of comments, pure praise did not have to be accurate to work. Positive comments produced just as much liking for the flatterer when they were untrue as when they were true.

- Contact and cooperation: We are more favorably disposed toward the things we have had contact with.

Conditioning and Association

There is a natural human tendency to dislike a person who brings us unpleasant information, even when that person did not cause the bad news. The simple association is enough to stimulate our dislike.

On the other hand, positive association can be leveraged to help increase the chances of being liked or favored. One common strategy is to link celebrities to the product.

Defense of others to leverage liking

we have to be sensitive to only one thing related to liking in our contacts with compliance practitioners: the feeling that we have come to like the practitioner more quickly or more deeply than we would have expected. Once we notice this feeling, we will have been tipped off that there is probably some tactic being used, and we can start taking the necessary countermeasures.

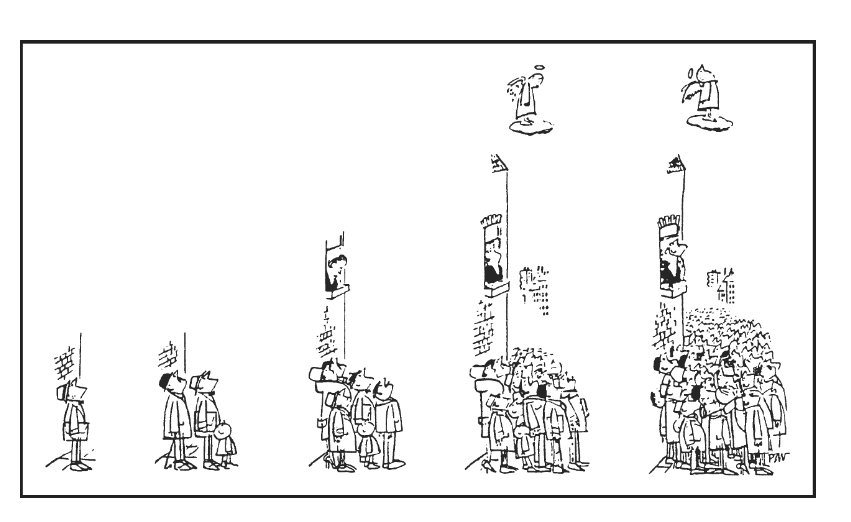

Chapter 4: Social proof: Truths are us

Popularity principle. People tends to follow the majority. As a heuristic, people would make fewer mistakes by acting in accord with social evidence than by acting contrary to it.

The problem comes when we begin responding to social proof in such a mindless and reflexive fashion we can be fooled by partial or fake evidence. Our folly is not that we use others’ behavior to help decide what to do in a situation; that is in keeping with the well-founded principle of social proof. The folly occurs when we do so automatically in response to counterfeit evidence provided by profiteers.

The greater the number of people who find any idea correct, the more a given individual will perceive the idea to be correct.

For social proof, there are three main optimizing conditions:

- When we are unsure of what is best to do (uncertainty).

- When the evidence of what is best to do comes from numerous others (the many).

- When that evidence comes from people like us (similarity).

Uncertainty

when we are unsure of ourselves, when the situation is unclear or ambiguous, when uncertainty reigns, we are most likely to accept the actions of others—because those actions reduce our uncertainty about what is correct behavior there.

The many

The seeming appropriateness of an action is importantly influenced by the number of others performing it.

- Validity: Following the advice or behaviors of the majority of those around us is often seen as a shortcut to good decision-making.

- Feasibility: If we see a lot of other people doing something, it doesn’t just mean it’s probably a good idea. It also means we could probably do it too.

- Social acceptance: We feel more socially accepted being one of the many.

We are more inclined to follow the lead of our peers in a phenomenon we can call peer-suasion.

Defense

- Sabotage: we can cruise along trusting in the course steered by the principle of social proof until we recognize that inaccurate data are being used. Then we can take the controls, make the necessary correction for the misinformation, and reset the autopilot. With no more cost than vigilance for counterfeit social evidence, we can protect ourselves.

- Looking up: an autopilot device, like social proof, should never be trusted fully; even when no saboteur has slipped misinformation into the mechanism, it can sometimes go haywire by itself. We need to check the machine from time to time to be sure that it hasn’t worked itself out of sync with the other sources of evidence in the situation—the objective facts, our prior experiences, and our own judgments.

Chapter 5: Authority: Directed deference

We are trained from birth to believe that obedience to proper authority is right and disobedience is wrong.

We rarely agonize to such a degree over the pros and cons of authority demands. In fact, our obedience frequently takes place in a click, run fashion with little or no conscious deliberation. Information from a recognized authority can provide us a valuable shortcut for deciding how to act in a situation.

Connotation, not content

- Title: Titles are simultaneously the most difficult and the easiest symbols of authority to acquire. To earn a title normally takes years of work and achievement. Yet it is possible for somebody who has put in none of the effort to adopt the mere label and receive automatic deference.

- Clothes: a series of studies indicates how difficult it can be to resist requests from figures in authority attire.

- Trappings: Finely styled and expensive clothes carry an aura of economic standing and position. People judge those dressed in higher quality apparel, even higher quality T-shirts, as more competent than those in lesser quality attire—and the judgments occur automatically, in less than a second.

The credible autority

People are usually happy, even eager, to go along with the recommendations of someone who knows more than they do on the matter at hand.

- Expertise: we have already chronicled the ability of expertise to exert significant influence, it’s not necessary to review the point extensively.

- Trustworthiness: Rather than succumbing to the tendency to describe all the most favorable features of a case upfront and reserving mention of any drawbacks until the end of the presentation (or never), a communicator who references a weakness early on is seen as more honest. The advantage of this sequence is that, with perceived truthfulness already in place, when the major strengths of the case are then advanced, the audience is more likely to believe them.

Defense

A fundamental form of defense against the problem, therefore, is a heightened awareness of authority power. When this awareness is coupled with a recognition of how easily authority symbols can be faked, the benefit is a properly guarded approach to authority-influence attempts.

- Authoritativeness: The first question to ask when confronted with an authority figure’s influence attempt is, Is this authority truly an expert? The question focuses our attention on two crucial pieces of information: the authority’s credentials and the relevance of those credentials to the topic at hand.

- Sly sincerity: How truthful can I expect the expert to be? Authorities, even the best informed, may not present their information honestly to us; therefore, we need to consider their trustworthiness in the situation.

Chapter 6: Scarcity: The rule of the few

Under conditions of risk and uncertainty, people are intensely motivated to make choices designed to avoid losing something of value—to a much greater extent than choices designed to obtain that thing.

Scarcity: Less Is Best and Loss Is Worst

When a desirable item is rare or unavailable, consumers no longer base its fair price on perceived quality; instead, they base it on the item’s scarcity.

- Limited numbers: The intent was to convince customers of an item’s scarcity and thereby increase its immediate value in their eyes.

- Limited time: This tendency to want something more as time is fading is harnessed commercially by the “deadline” tactic, in which some official time limit is placed on the customer’s opportunity to get what the compliance professional is offering. A variant of the deadline tactic is much favored by some face-to-face, high-pressure sellers because it carries the ultimate decision deadline: right now.

Psychological reactance

Like the other weapons of influence, the scarcity principle trades on our weakness for shortcuts. We know that things that are difficult to get are typically better than those that are easy to get. As such, we can often use an item’s limited availability to help us quickly and correctly decide on its higher quality, which we don’t want to lose. Thus, one reason for the potency of the scarcity principle is, by following it, we are usually and efficiently right.

Optimal conditions

Not only do we want the same item more when it is scarce, but we want it most when we are in competition for it.

Defense

The joy is not in the experiencing of a scarce commodity but in the possessing of it. It is important that we not confuse the two. Whenever we confront scarcity pressures surrounding some item, we must also confront the question of what it is we want from the item. If the answer is that we want the thing for the social, economic, or psychological benefits of possessing something rare, then, fine; scarcity pressures will give us a good indication of how much we should want to pay for it—the less available it is, the more valuable to us it will be. However, often we don’t want a thing for the pure sake of owning it. We want it, instead, for its utility value.

Chapter 7: Commitment and consistency: Hobgoblins of the mind

Once we make a choice or take a stand, we encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to think and behave consistently with that commitment. Employee commitment is highly related to employee productivity.

Inconsistency is commonly thought to be an undesirable personality trait. The person whose beliefs, words, and deeds don’t match is seen as confused, two-faced, even mentally ill. On the other side, a high degree of consistency is normally associated with personal and intellectual strength. It is the heart of logic, rationality, stability, and honesty.

The tactic of starting with a little request in order to gain eventual compliance with related larger requests has a name: the foot-in-the-door technique.

Every time you make a choice, you are turning the central part of you, the part that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before. —C. S. Lewis

People have a natural tendency to think a statement reflects the true attitude of the person who made it. What is surprising is that they continue to think so even when they know the person did not freely choose to make the statement.

Once an active commitment is made, then, self-image is squeezed from both sides by consistency pressures. From the inside, there is a pressure to bring self-image into line with action. From the outside, there is a sneakier pressure—a tendency to adjust this image according to the way others perceive us.

Most people have the desire to be and look consistent within their words, beliefs, attitudes, and deeds.

Within the realm of compliance, securing an initial commitment is the key. People are more willing to agree to requests in keeping with the prior commitment.

many compliance professionals try to induce people to take an initial position that is consistent with a behavior they will later request from these people.

Commitment decisions, even erroneous ones, have a tendency to be self-perpetuating because they can “grow their own legs.” That is, people often add new reasons and justifications to support the wisdom of commitments they have already made.

Another advantage of commitment-based tactics is that simple reminders of an earlier commitment can regenerate its ability to guide behavior, even in novel situations.

To recognize and resist the undue influence of consistency pressures on our compliance decisions, we should listen for signals coming from two places within us: our stomachs and our heart of hearts. Stomach signs appear when we realize we are being pushed by commitment and consistency pressures to agree to requests we know we don’t want to perform. Heart-of-heart signs are different. They are best employed when it is not clear to us that an initial commitment was wrongheaded.

Chapter 8: Unity: The we is the shared me

People are inclined to say yes to someone they consider one of them. Factors of “we”: kinship, race, religious, cultures, political view, place and locality, etc.

From an evolutionary perspective, any advantages to one’s kin should be promoted, including relatively small ones. Besides physical comparability, people use attitudinal similarities as a basis for assessing genetic relatedness and, consequently, as a basis for forming in-groups and for deciding whom to help.

Approaches to bring unity: like, support, trick fast & slow thinking, repeated reciprocal exchanges, suffering together, co-creation, asking for advice.

Leave a comment